Makor Rishon Interview with OUI President Prof. Leo Cory: Open to Change

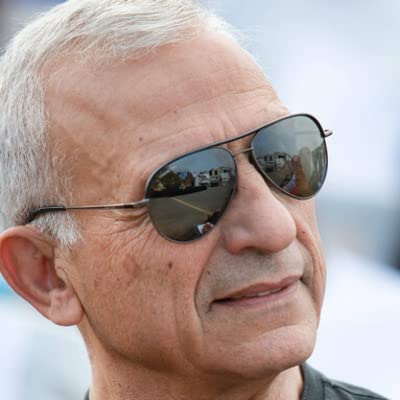

It has not been an easy year for Leo Corry, President of the Open University of Israel. A quarter of his students have been called up for military service, university researchers are being boycotted by colleagues abroad, and exam centers have closed due to a lack of bomb shelters. And overshadowing everything is his personal grief over the massacre at Kibbutz Nirim, his first home in Israel. As the second academic year in the shadow of war begins, President Corry talks about the challenges that artificial intelligence poses for examiners, and his conviction that all universities will soon copy the Open University model.

Prof. Leo Corry’s first encounter with the Open University of Israel (OUI) was in 1977, thanks to the brown envelopes that made their way to all parts of Israel, including Kibbutz Nirim.

Corry was then a young man of 21 who had just arrived in Israel as part of a group of new immigrants organized by the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. “The Open University had been founded only three years earlier, in 1974, and several textbooks circulated among kibbutz members who had enrolled for courses. I remember the deep impression that their quality made on me. But I was no less impressed by the logistics involved in the operation of the OUI. We were a small, remote kibbutz in the Negev, and the university monthly assignments would arrive in envelopes by regular mail; the [kibbutz] members would work them out, send them back to the OUI, and a week later receive answers. I fully understood back then the important social role this institution played – to make higher education accessible to all levels and sections of Israeli society. That was the mission of the university when it was founded, and even though life has changed a lot since then, it is still its mission today.”

Four and a half decades later, with a long and accomplished academic career to his credit, Corry was invited to serve as president of the Open University – and discovered that the task of making education accessible was going to be more difficult than ever. He took office on October 10, 2023, only three days after the outbreak of war. “At the time of the attack I was with my wife in Paris, where I had been invited to give a lecture. In the morning, reports began to arrive, and I heard what was happening in Nirim, where so many friends and family live. I wrote to my son that something terrible was happening, that terrorists had entered Nirim. He replied that the situation was much worse than I could imagine that the incursion was not only into Nirim but to all settlements around the Gaza border. He sent me the famous video clip showing a Hamas reporter broadcasting from Nir Oz’s central lawn. We also began to receive the names of murdered victims and missing persons – family and friends. It sounded like a terrible situation, even though the real dimensions of the tragedy were yet to be disclosed.”

He points to two pictures hanging in his office – photos of Nadav Popplewell and Yagev Buchshtav, who were abducted and murdered in captivity. “They are both children of my neighbors who grew up door to door with my house in Nirim. Although we left the kibbutz a long time ago, we keep strong contacts with many families. The communities in the Gaza Envelope region are very strong, everyone knows everyone else. As a high-school teacher in the regional school I taught many of those who were killed or taken hostage. I was also involved in the economic life of the region and worked along with members of other kibbutzim, particularly Nir Oz, one of the most deeply affected ones in the massacre.”

Despite the chaos and the tragedy, Corry arrived, as planned, for his first day at the new job in the OUI. “There was a lot of tension within the university because of the situation. Weighty decisions had to be made, and at that stage I was not yet fully familiar with how the university functioned. For example, I suggested moving the dates of some exams, because of the situation, and I was told “You have no idea of what you’re talking about. An exam day at the OUI is like a military operation that begins at 6:00 a.m. and ends in the middle of the night. The same questionnaire must be distributed simultaneously to study centers throughout the entire country and sent back to the Raanana campus at the end of the day. Locations are rented months in advance, taking into account logistic and security considerations … This is just one example of the peculiarities of the OUI and the way it works, that I had to become acquainted with much faster than I thought I would.”

The first and most important decision to be made, Corry says, was when to open the academic year. Although all university heads have tried to make major decisions jointly throughout the past year, studies at the Open University commenced on December third, three weeks before all other institutions. “In retrospect, I regret that we didn’t begin even earlier than that. The decision to postpone the start of the academic year was based on the fact that many students were mobilized to reserve duty, and we didn’t want them to fall behind. But I said from the beginning that this was not the Six Day War, and that it would take months before there would be massive releases of reservists. Little could I know that more than one year the situation has become only more complicated. At OUI, we teach close to 50,000 students, of whom 10,305 are reservists. We are fully committed to the soldiers, but in such a sensitive and unstable situation, people who are not in the front need anchors in their lives, and studies help to create order amid the chaos, including for many families of reservists. I thought that opening the academic year was a moral duty. As soon as we began the semester, 38,000 students registered. We have found ways to support the reservists with scholastic adjustments, financial aid, the option of canceling courses without incurring fees, etc.”

Corry knows from personal experience the negative impact of a lengthy reserve duty on the course of studies and the great effort needed to overcome it. In the first Lebanon war of 1982, as he was about to complete his M.Sc. studies in mathematics, he was mobilized for two long periods of 45 days, which deeply disrupted the routine. The Open University is fully committed to support the reserve soldiers, who are now serving periods that in occasions reach more than 200 days, and the big challenge is how to provide the necessary support with minimal negative impact on the level of study and academic demands. As it is based on independent study and online resources that make it possible to maintain continuity of studies even when normal life is disrupted, the Open University is inherently structured to meet this challenge in a reasonable way. In addition, core courses in all tracks are offered every semester, and the degree programs are structured in a very flexible way. Thus, if a student cannot join a certain course due to reserve duty or difficulty in readapting to the normal civil life, can take it later and will not have to forfeit an entire academic year.

“Nevertheless—Corry stresses—military service takes a toll. There are no administrative solutions that can counter the march of time, so that we have had to be flexible in many ways.” Corry accepts and deals with the reservists’ complaints, but according to him politicians are trying to take advantage of the situation to attack academia, and this is harder for him to accept. “I was invited alongside two other university presidents to a debate in the Education Committee of the Knesset, and they virulently attacked us as if we were the enemies of the people. They said that we have no consideration towards the students, that we have lost touch with reality and that we live in an ivory tower. It so happens that the other two presidents are former fighter pilots, and I was a combatant in the Nahal brigade. The soldiers are also our children, friends of our children or children of our friends. We live inside our people. I didn’t understand what they were talking about in the committee; it was very unpleasant. I don’t mind being yelled at; I hold a public office and it’s part of the deal. But it’s totally unfair to all the university staff who have been working so hard around the clock to take care of 11,000 students who are entitled to concessions due to Operation Iron Sword. To sweepingly belittle them and promote political interests at the students’ expense is malicious and unacceptable.

“If we fail to address every problem of individual students or every case that is brought to our attention, it is not because we are disconnected, but because the situation is difficult and complex. For example, there were complaints about the closure of examination centers in the north. In actual fact, this was due to instructions of the Home Front Command, because the classrooms did not meet the standards for protection against missile attacks. Finding other classrooms in the region was, and is, complex, because these are long-term contracts. I realize that [finding alternate arrangements] is not the students’ problem. They have studied and they want to take their exams at a convenient location, so we tried hard and worked around the clock. In most cases we managed to find solutions, but sometimes we also made mistakes.”

Now another academic year is beginning in the shadow of the battles, and the rumbling of war continues to have a profound effect on Corry’s agenda. The center of gravity has shifted from Gaza to Lebanon, and once again, one out of four Open University students is involved in defending the country. Although Corry is convinced that he and his colleagues are wiser today than they were before, he is very worried about what he sees around him. “The reservists and their families are exhausted. The atmosphere is heavier, and the students’ financial situations are worsening. The situation is worse than it was a year ago. But even with all the complexities involved, we have managed to maintain a continuum of studies. I wholeheartedly believe that the continuation of life and our students’ development within the complex situation we find ourselves in is essential for thinking about rebuilding the future of Israeli society.”

The Question That Embarrassed the Teachers

Corry, 68, came to Israel in 1977 from Venezuela, where he grew up in the Jewish community and received his education in the local Jewish school. He joined an aliyah group when he was already a university graduate with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. “I grew up in a Zionist family, who knew that they intended to immigrate to Israel. And indeed, my mother and sister also came to Israel after me; my father passed away in Venezuela before he could realize his dream, whereas my brother stayed there.”

His group settled in the Negev, in Kibbutz Nirim. From there, Corry went on to combat service in the Nahal brigade, and then for six years he worked as a farmer. He was in charge of the irrigation system of one of the biggest farms in Israel at the time; 23,000 dunams (5600 acres) of crops. “It was hard physical work which I truly loved. We mostly grew cotton, but there were other field crops such as potatoes, peanuts, and carrots. I would get up early in the morning and drive a jeep in the fields alongside the wild animals and birds, listening to classical music.”

In Nirim he met his wife, Efrat. “We started our family in the kibbutz and lived there until 2000.” Today they go every Saturday to Hostages Square to visit Kibbutz Nirim’s corner. “Today the kibbutz members are temporarily living in Beersheva, so the people who come to the square are mostly those who have left, and we meet and talk. It’s hard to explain the relationships still dominant among people who were part of a kibbutz communal life. It’s very special, certainly under such extreme circumstances.”

Alongside work in agriculture, Corry taught and held educational positions in the regional school, while completing a master’s degree in pure mathematics at Tel Aviv University. Just when he was starting to think about a doctorate, the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Ideas was established at the university and Corry joined it immediately. Alongside kibbutz life, he advanced his career in the academic world. For a while, he was serving as a university faculty member and kibbutz secretary at the same time.

His academic career included a series of distinguished positions – head of the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Ideas, editor-in-chief of Cambridge University’s prestigious journal Science in Context, and head of Tel Aviv University’s School of History and dean of the Faculty of Humanities. He was invited professor fellow at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin, MIT, and the ETH in Zürich. “I discovered that I prefer to look at science, particularly at mathematics, from an historical perspective; to identify historical processes in the development of scientific knowledge, rather than to create new mathematics. This was my tendency from childhood, and I always asked the teachers at school ‘How did the scientists arrive at this?’ Honestly, they didn’t always know the answer.

“Today I have the tools to understand the significance of the processes of knowledge change and creation. When the first universities were established, around the thirteenth century, the new kind of institution allowed a fundamental change in the development of knowledge. It was not that people became smarter, but the university and its organization facilitated real progress. Today we are once again in a period of far-reaching changes, especially since the development of AI. The Internet has drastically changed the essence of scientific collaboration, and therefore, science itself has grown in unprecedented ways. Previously, disseminating new ideas and creating longstanding collaborations involved difficulties that have disappeared since the mid-1990s. The spread of knowledge has become much faster, as well as the building of collaborations and the exchange of ideas. It is too early to say what the impact of AI will be, but there is no doubt that it will profoundly change the world of science. Two Nobel Prizes – in physics and chemistry – were awarded this year to people who deal with artificial intelligence, because it is clear that developments in this tool is redefining the rules of the game.

“Many ethical questions arise relating to who controls scientific knowledge and how research agendas are defined. But you cannot ignore technological progress; you have to learn how to use it properly. I have experienced quite a few examples of this in my life. When the use of email became common, I had colleagues here in Israel who declared that they would never send an email because ‘it is too impersonal’. Well, I would not blame anyone in retrospect nor remind people of what they said back then, but I found it amusing then, and even more amusing now. This approach also applies to the simplest technologies, whether writing ‘notes’ or searching for documents and journals in digital archives, which is best done with the help of digital tools. And it also applies to much bigger things, such as AI.

“In any case, it is too soon to say what the changes will be or what the future will hold. It is absolutely clear that AI is not just another innovative tool like a word processor or even the Internet as a whole. There are people who like to predict the future. As a historian, I feel comfortable looking at the past, and being careful about predicting the future. In any case, heads of universities and the leaders of the academic world must confront these questions, understand how to deal with, and prevent problems, and on the other hand, devote a lot of thought on questions related to harness these new technologies to fit our needs.”

Without Partners, there is no Money

When he was about to conclude his position as dean at Tel Aviv University, Corry was already planning to retire and realize many dreams. Two unexpected factors, a broader one and a personal one, suddenly caused him to change course. “Throughout 2023, Israel was in turmoil. All of us, regardless of which side of the political map we were on, asked ourselves what we should do in view of what was happening in the country. I could have become emeritus and perhaps become active in some kind of political or civil activities. But then the opportunity arose to accept the position of President of the Open University.” He had previously collaborated sporadically with the Open University – it was the first place where he had taught in Hebrew in the early 1980s, and later he also developed a course for the OUI. “Now it was clear to me that if I took the position, this will give me the possibility of making a real difference for Israeli society in such challenging time. I decided to go for it. Little could I know that the real challenges for our society were still ahead.”

The war brought with it a wave of anti-Israeli activities, and sometimes open anti-Semitism, on campuses abroad. Corry admits that he feels their impact. “Many academic institutions and individuals from around the world refused to collaborate with us even before the war, but now it has worsened. Already twenty years ago, in fields such as anthropology or Middle East Studies, our colleagues would submit papers and were ignored. Now we see how academics and researchers who used to have connections in Israel have also withdrawn from contact. Today it is difficult to find research partners; without a partner it is impossible to submit applications for international funding; without money it is impossible to conduct research, and then you are also not invited to conferences. This seriously harms young researchers, who will have difficulty developing their careers.

“In addition to the academic side, protests began on campuses abroad against guest lecturers and Israeli and Jewish students. We are facing a deeply challenging geopolitical situation, and things are not changing for the better. International organizations and Qatari money are also involved in this. We need to be aware that both in the USA and Europe, there are intergenerational societal changes concerning the level of support for Israel, even within the Jewish communities.”

Here in Israel, there have been statements by university lecturers that some in the public opinion have described as expressing “anti-Israeli sentiments”. Corry completely dislikes law proposals requiring universities to sanction and suspend such lecturers. “Academia should be free from politics. Therefore, we act under the Council for Higher Education, whose role it is to create a buffer between us and the political echelon,” he says. “This separation is very significant. For example, the government passes a budget, and the Budgeting Committee distributes it based on its professional point of view. There are also political considerations, but at least the politicians do not have a foothold in academic decisions. The new law proposals involve attempts to break down this buffer and intervene politically in what happens inside academia.

“In addition, Israel has a law against incitement – so let the authorities apply it. How can I know what falls under the category of incitement? That’s why there are law enforcement agencies. A university president is not a law enforcement agent. The proposed legislation is meant to signal the universities as enemies and traitors. This is unacceptable and has nothing to do with reality in the Israel academy. Following the massacre of October 7, there were two incidents of statements by university professors, that many considered inappropriate. Most university professors strongly opposed them, but only a court can determine whether they were considered incitement, and in fact none of the professors was indicted. Just because two professors said things that some people strongly disliked, it doesn’t mean that academics are the enemies of the people.”

A Credit Card and a Pulse

The Open University is marking its fiftieth anniversary this year. Since its establishment, it has been guided by two principles, says Prof. Corry: The first is accessibility and open acceptance for studies, and the second is maintaining the highest academic standards. “We are one of nine research universities in Israel,” he says proudly. “Our courses are acknowledged by all the other institutions; however, we do not have admission criteria: you just need an ID card, a credit card, and a pulse. We are flexible in terms of building a degree program. Each student advances at their own pace, but when it comes to meeting the course requirements, we are very strict and totally inflexible.”

It is important for Corry to clarify that the basis of the university’s activity is not “online studies” but rather “independent, distance learning”. “It’s true that we also rely on online methods, but the idea is to build, for each course, an entire ecosystem that includes a textbook that is carefully worked out by a dedicated team, and a sophisticated website on which the entire material is provided and interaction with the course coordinator is performed. This allows us to reach all types of populations – outstanding high school students, elite IDF units, peripheral areas, ultra-Orthodox Jews, Arabs, mainstream students … everyone. We have almost 4,000 ultra-Orthodox students, which is more than all the other universities combined. We have learned to work with this population because we offer a framework that is suited to them, and we are the best solution for higher education for ultra-Orthodox students. We are also becoming stronger in Arab society, but we still have more to work harder on that front. The expansion of higher education in these two populations is our stated goal, and it is a national mission as far as we are concerned. At the same time, 35% of our student body is in computer science, and 40%is in STEM. It is important to note that in trying to reach broad populations, we do not by any means compromise on our academic standards. If you lower the requirements, then sure, you can bring hordes of students, but that’s not what we are here for. Without insisting on academic excellence and high standards, we do not fulfill our stated aims.”

Today, when other institutions have also been transitioning to hybrid studies, does it threaten your uniqueness and attractiveness?

“Many organizations use distance learning, but we are the only ones who do it professionally, because it is our essence. Apart from independent study, we have class meetings, 80 percent of which are on Zoom. We have been using Zoom since 2014, and when the COVID 19 pandemic started, everyone came to us to learn how to do it. But it’s not just about Zoom – we also have a system that tracks the progress of each student in each course, so that we know in what areas we can help them, and it tells us if there are problematic parts in the course itself. We are experimenting with future technologies, such as AI or virtual reality, so that when they break through, we will already be there and know how to use it in wise ways. This helps us, for example, to guide students throughout the degree on the basis of information we have about their studies in previous courses.”

Are you concerned that artificial intelligence will make academia redundant? After all, it can give you whatever knowledge you want, and also hold discussions with you.

“It is possible that AI will make some parts of the academic world redundant in its present form, but we inherently do not work in a traditional form of academia, and in the not-too-distant future all universities will follow models that will be close to what we already do today. That is, if you want to teach 5,000 students a course on Java programming language, you have to do it as we do: a professor that leads the team and sets the standards together with a team who work together to build the course, a teaching coordinator who is responsible for the operation of the course, and students who are assigned to small groups led by instructors. This is a completely scalable and sustainable model.”

But why would students learn Java at all? They’ll use AI.

“That’s a serious mistake. They may not need this particular programming language, but they will have to know the programming languages of artificial intelligence and the very idea of working with computers. The programming world will change, but it is not going to vanish. It will only become more central to all what we do. You have to learn what it means and what the future will look like. I learned programming with punch cards; some times I use to drop them and hated that. Probably that was a strong reason why I did not follow in the computer science track, which was quite novel at the time, and went along with pure mathematics, which is what I truly loved. But since then, everything has changed a thousand times already and studying computer science and programming is something quite different from what it was back then. People programmed in the past in machine language, afterwards came high-level programming languages, object-oriented languages, and then more advanced ones. Programming in AI environments will involve some new approaches that people will have to learn accordingly.

“But apart from all this, the most important point in my view is that studies are not just an instrumental tool. Studies are a means for enriching the soul, and this is the main justification for continuing developing the scholarly world. You can follow an instrumental approach concerning what you study, and that’s very good in itself. But if this is the only thing you get from your studies, that I feel sorry for whoever does this. Your world is richer and more beautiful the more you learn about literature or biology or Jewish thought. The main role of universities is to help educate better citizens and people with richer inner lives. We need programmers, of course, but first of all, we need good citizens who know how to read a newspaper critically, regardless of which political side they are on. We need people who do not live according to tweets or talkbacks, but people who are read and write properly. This is now much more necessary than in the past, because we are inundated with unreliable information. The richer a person’s mind and spirit, the better it will be for them and for society. That’s how it always has been and that’s how it must remain, with or without AI.”

Nevertheless, Corry admits that there are many challenges with the new reality. Open University examiners use a program that detects whether the answers in exams or papers have been copied from the internet, and students are very ingenious in finding ways around. “This is a kind of stupid cat-and-mouse game. We will have to find more radical solutions that give a different perspective of how exams are conducted. There are basic skills that we cannot do without, such as reading and writing. People do not know how to write, and we need to focus on this, even if we use smart tools to help the process.

“As a child, I knew how to do complicated calculations in my head in seconds, and I remembered the telephone numbers of all the children in my class; today I can hardly remember my wife’s phone number (actually I do). There is a trade-off: Technology enables us to do things much better and much faster, but we are losing other capabilities. The challenge of AI is especially great, because it touches on what we thought was the advantage of humans over machines, and suddenly it emerges that this may not be the case, and perhaps we will have to redefine these limits.”

These are questions for the humanities – a branch that is already losing ground, and the number of students who choose to focus on it is shrinking. As someone who was Dean of Humanities at Tel Aviv University, do you see a future for this academic field?

“When I entered that role in 2015, I was very explicit in saying that we all have to declare that there is no crisis in the humanities. No one likes to join a team of losers that are al the time complaining. There may be a crisis in enrollment in BA tracks in the humanities, but the intellectual disciplines of the humanities are thriving. There are many excellent researchers at the higher levels, and in fact much more than the number of available academic positions. There are administrative questions about how to maintain a department in a university when there are so few undergraduate students. My answer is that we must select the researchers carefully and invest in them so that they will be at the top of academic research worldwide. That is what universities are for. Also in the departments of pure mathematics around the world enrollments are low. Would anyone think of closing those departments? I really hope not, because they have a deep academic value. The same should apply for the humanities.”

At Tel Aviv University we had a serious problem with Jewish studies, to indicate one interesting case. Some authorities thought that the school of Jewish studies should be closed because there were few students. I don’t come from a religious background, but I’m a Zionist and a Jew, and I said that it was unthinkable that Tel Aviv University would not have a department that teaches Bible studies, Jewish thought, or Semitic linguistics, and top researchers in those fields. Otherwise, what is the justification of a university in tel Aviv? Without this department, we might as well close up business. People can study chemistry or engineering abroad. At the Open University we are also engaged in strengthening Jewish culture by publishing, for example, remarkable book series on Hebrew literature and Jewish thought. Without this we have no justification for our existence as a university in Israel. Of course, concrete questions may arise, such as how many researchers or scholarships there should be in fields in the humanities, but first, we must have the understanding that we are here for those fields and especially for those related to the Hebrew culture and Jewish culture. A university without the humanities is not a university.”

The Future Is Open.

Support the Open University of Israel Today.