A Delicate Tapestry of Israeli Society

“I lived in the Gaza border community for over twenty years, as a

member of Kibbutz Nirim. All of the experiences of my life in this country

are full of contexts related to the communities in this region; the

landscapes, and the scents that change with each passing season. . .

Disappointment, anger, shock, and uncertainty are always present in our

lives, and each of us searches for ways of coping with them.”

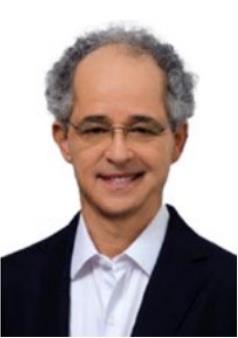

Professor Leo Corry, President of The Open University, thirty days after the massacre.

Photo: Tomer Jacobson

Dear friends, dear OUI community, and dear students,

Today, the entire country is commemorating thirty days since the dark day that changed the face of this land forever. On Saturday morning, October 7, 2023, on the festival of Simhat Torah, the wall separating the Gaza Strip and the communities adjacent to Gaza collapsed. On that day, exactly fifty years after the collapse of the famous “operational concept” that paved the way for the Yom Kippur War, the political “concept” that the government followed for the past twenty years also buckled. As it fell, it pulled down with it the sophisticated warning systems and the towering walls that cost billions of shekels and took many years to build, and that were meant to protect the border and the residents in the border communities. The lives of over 1200 Israeli civilians, soldiers, and police officers also collapsed, as did the lives of foreign citizens who were working in the region. The lives of thousands more were destroyed – those who were kidnapped, missing, physically and emotionally injured, and the continuously growing circle of relatives and friends who surround them; plus “ordinary” worried citizens. Entire communities collapsed, as residents of whole towns and neighborhoods were forced to abandon their homes and move in with family members, or relocate to temporary accommodations in hotels or with kind people in other areas of the country for an indefinite period of time.

Those of us in the towns and communities on that terrible day, and those of us watching from afar, had all grown up on values such as love of the land and its people. Together, we experienced the shattering of basic ideas that had imbued our lives with meaning, here in this complex and difficult country. Above all, destroyed was our belief that no matter how difficult the situation and how serious the threat, there would always be somebody – the army, the police, fire fighters, and ordinary citizens – to help us and rescue us from attack. The stories of the bravery of those who rescued others, sometimes while sacrificing their own lives, are still being revealed every day, and they arouse feelings of awe and gratitude. For many residents of the south, however, this assistance came too late, or not at all, and many felt abandoned. Long before the fence was breached, they had felt ignored by state institutions and leaders, even as surprising and powerful displays of solidarity crossing sectoral lines are led by organized groups of ordinary citizens. These individuals are investing their time, energy, and money, and going the extra mile to help evacuees and all of those affected. Many citizens are supporting and encouraging the families of the hostages and the missing, whose suffering is indescribable. Meanwhile, our leaders seem incapable of assuming responsibility for their actions and blunders, rising above petty politics, or understanding the critical nature of the times.

Disappointment, anger, shock, and uncertainty have become ever-present in our lives, and each of us is searching for ways to cope, sometimes successfully and sometimes less so. Many young adults are currently serving in the reserves and fighting in the war, in both the north and the south, while the terrorist organizations in the Gaza Strip and the north continue to fire rockets and wreak physical and mental destruction.

As we mark thirty days since that black Shabbat, we must, above all, remember our dead, the missing, and the hostages; not abstractly and as part of terrifying statistics, but as individual human beings whose lives each represented an entire world that was destroyed. We must remember these individuals and tell their stories, beyond the horrific experiences and collective trauma of that dark day. Each person has a name, and each of us thinks of the specific people that we knew; the stories we saw or heard that are etched into our hearts. I would like to briefly share with you my thoughts about a number of people who had first names and last names, who I knew or still know. Within the greater tragedy, I connect with their personal tragedies.

I lived in the Gaza border community for over twenty years, as a member of Kibbutz Nirim. All of the experiences of my life in this country are full of contexts related to the communities of this region; the landscapes, and the scents that change with each passing season. Significant years of my life were filled with memories connected to many of the casualties, the hostages, and the missing people and their families. I think, for example, of the long list of casualties from Nir Oz, the kibbutz next to Nirim, and to those who are still missing. It was one of the communities most severely hit on that dark day.

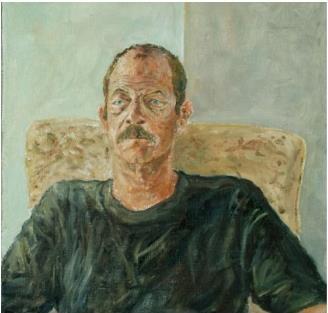

I think about eighty-year-old Carmela Dan, a wonderful woman I met during my first days in Israel, with whom I sang for years in the excellent regional choir. I saw the photo of her with her lovely granddaughter Noya, who was on the autistic spectrum – a photo that broke the hearts of many in Israel and worldwide. I think about Yocheved Lifschitz and Nurit Cooper, who were released from captivity, and about their spouses, Oded Lifschitz and Amiram Cooper, who were not. Amiram wrote the beautiful lyrics to the song “Sheaves of Gold,” which has been proudly performed at every kibbutz harvest ceremony around the country over the years. I also think about Chaim Peri, whose photo appeared on the front page of Haaretz newspaper’s Gallery magazine on November 7. This bohemian kibbutznik and sixties relic founded an exceptional, almost fantastical, art gallery on the border between the fields of his kibbutz and those of Nirim. They, and many others, whose photos appear on the signs demanding their immediate release from captivity, were born slightly before the establishment of the State and were founders of the kibbutz. Their stories are the stories of the history of this country, through all of its stages and all of its wars. They built a wonderful community in Nir Oz, even as it was targeted by rocket fire for the past twenty years. Since the eighties, these kibbutzim have also been targeted by criticism that calls them “parasites living at the State’s expense,” even as they plow the Negev soil and build successful enterprises. Their communities, along with the rest of the kibbutz movement, experienced a severe economic and ideological crisis at the end of the 1980s, yet made an impressive comeback. If they are not rescued from the Hamas cellars, their lives are liable to end in Gaza, and not in the tidy cemetery of their own community.

I think about the casualties and hostages of Kibbutz Nirim; of the worlds that were destroyed, even though Nirim had “only” four hostages and four casualties, and was therefore impacted less than its neighbors. One of the hostages is Yagev Buchshtav, the son of Oren and Esther, who were my neighbors for many years. I remember when Yagev was born, and I knew him as he grew up in the house next door. Yagev was a special, inquisitive boy who grew up to be a talented musician. He was kidnapped with his partner Rimon, who we all remember from the horrific video that Hamas publicized. A young couple, thirsty for life, with the whole world before them. My neighbors at the other end of the building were the unique Popplewell family. Roy, the older brother, was murdered outside their home. Roy was an energetic boy, always testing the limits, and none of that changed when he grew up. He probably resisted those who tried to kidnap him, and they eventually killed him. His mother Hanna (Note: released from captivity after 49 days), and brother Nadav were kidnapped. Nadav was a computer genius at a time when most of the world did not even own personal computers. He was a “geek,” before the term became popular. I was privileged to be his teacher in high school, and then watch him in action as a professional. He was carefree in his appearance and actions, but the sophisticated code he wrote in many programming languages almost read like lyrical prose. I recently remembered that we wrote a patent together in the field of electronic data storage, and I am proud, and now moved, as well, that I had the privilege of working with this special man. Where is he and where is his elderly mother now? Who is taking care of them? What are they undergoing? Do his captors have any idea that this man, whom they are holding prisoner in a dark cellar, has sought peace with his neighbors on the other side of the fence his entire life and brought only good into the world? Where are the babies and children who were kidnapped? Who is taking care of them? Who is feeding them? Together with the families, we hope for their speedy return.

I also think about Kibbutz Be’eri, which realized the dream of a collaborative, equal, economically and culturally flourishing society that benefits all of its members. Above all, I think about Marcel Frailich Kaplun and Drori Kaplun. Dror is the brother of my dear brother-in-law Yehuda, who is from Nirim and is currently staying with my sister-in-law Orna in Eilat with the rest of their community. Drori and Marcel were a fairytale couple, so special and loved by all; people who were the “salt of the earth” in the deepest and most beautiful sense. All connection with them was lost by ten o’clock that Saturday morning, and their fate is unknown. Marcel’s body was identified ten days after the massacre, and we still do not know what happened to Drori. (Note: Ever since the speech was held, Drori’s body has been identified and was buried in Kibbutz Mishmarot.)

I think of them, and of many others. Each of us focuses on stories connected to specific names, beyond the general pain and tragedy. In Sderot, Ofakim, Netivot, the Bedouin towns, the moshavim and the kibbutzim; communities that experienced challenges and shortages, and whose residents managed to build them with great effort over the years – the lives of women and men, children and adults, were changed unrecognizably on one dreadful day.

Those directly wounded; the soldiers and security forces who came to rescue others and were injured; those who are now far from their homes, must all somehow collect the broken pieces of their lives and start reorganizing for what lies ahead. It will not be easy, and for the more vulnerable members of society it will be even more difficult. There is no doubt that the Israeli civilian population will continue to provide support to the best of its ability, but the overarching responsibility for the rehabilitation of our country lies with the government institutions and the leaders, including those who refuse to recognize their responsibility and do not hesitate to pass it on to others. Our leaders need to not only patch the cracks of that day, but also, heal the divisions that formed over the months that preceded it. Let us not forget that the Open University community is also part of civil society and is a government institution. We too, are responsible for advancing the processes that will rebuild the lives of those affected and the delicate tapestry of Israeli society.

We would like to strengthen those serving in the army and their families. Our hearts are with the evacuees, the wounded, the hostages, and with their families, as well as with the families of those who were murdered. Over 1,200 life stories were cut short. May the memories of all of the casualties be a blessing.

Leo Corry

Short CV

My professional life has covered three main, separate contexts of activity that can be

briefly described as follows:

- Academic: My academic education was in pure mathematics, with a significant component in various fields of the humanities. My main field of research is in History and Philosophy of Science. I have published extensively on the history of modern mathematics, physics, and computing, and my work in these fields has been internationally acknowledged. My fields of academic interest also cover the history of science in Israel, the history of science in Latin America, the interplay between science and art, and the literary work of Jorge Luis Borges and of Alejo Carpentier. For more than a decade I was Editor in Chief of the prestigious academic journal Science in Context (Cambridge University Press). At Tel Aviv University, I was Dean of Humanities (2015-20), Head of the Yavetz School of Historical Studies (2003-09). Before tenure, I was also the acting academic coordinator of the Lautmann Inter-Disciplinary Program for Fostering Excellence (1990-94).

- High-Tech Industry: Between 1996 and 2020 I worked as consultant with various leading companies in the Data Storage Industry: EMC2 Corp., of Hopkinton, Mass., XIV Storage, IBM and Infinidat. I was involved in creating Knowledge Management Infrastructures for these companies, as well as managing and developing their patent portfolio. I co-authored 20 patents in data storage and software engineering.

- Kibbutz Nirim: Between 1977 and 2000 I was a kibbutz member. Among the most significant personal achievements that I can take pride of, some stem from my many years of active membership in Kibbutz Nirim and my involvement in both its economic and its social facets. In particular, I coordinated a highly demanding recovery program that took the kibbutz back from a deep crisis in 1985 (including a debt of about 100 million NIS), to full economic recovery and a renewed social impetus by the year 2000.